“Do we need to understand astrology in order to understand Shakespeare? It would be difficult to fully comprehend today’s television shows and movies without some knowledge of our modern world. There are references in these scripts to various aspects of life in our times which someone from a different time would be unable to appreciate. The same is true with respect to understanding Shakespeare and his works – timeless they may be, but they do nevertheless reflect modes of thinking that are, at least in some cases, specific to his time, including a general interest in astrology.” ~ C. J. S. Thompson

Shakespeare’s Audience

During Shakespeare’s time, astrology was in favor. Most courts employed an astrologer to aid when vital decisions had to be made, and astrology was used for calendars, medical purposes, horticulture, agriculture, navigation, and many other things.

People of the time purchased almanacs with the latest astrological forecasts for just a few pennies. These almanacs provided information about dates, high tides, and the moon’s phases, as well as predicting the weather for the year ahead. Millions of these almanacs were produced and sold.

Shakespeare was writing to an audience who could perceive, understand, and follow his astrological references since such knowledge was part of the mass consciousness of the Elizabethan Era.

The Elizabethan Era

Shakespeare lived during the height of the English Renaissance, often called “The Elizabethan Era.” People of this era believed in spirits of good and evil and supernatural arts, such as sorcery, sympathetic magic, and demonology. They used charms, white magic, and prayers to ward off evil. They believed the Earth was the center of the universe and that the positions of the planets affected everything in their daily lives. Elizabethans believed in astrology, and both nobility and commoners were familiar with basic astrological concepts of the time and had a rudimentary understanding of the language of astrology.

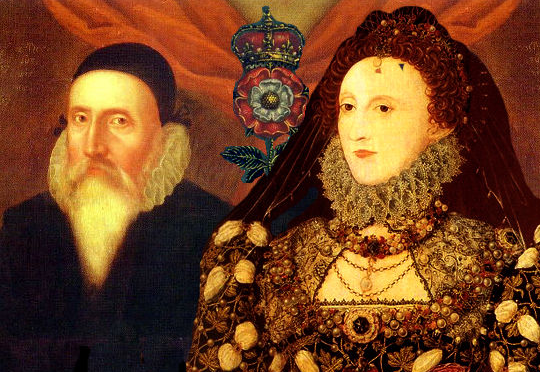

The era is named for Queen Elizabeth I, who used astrologer John Dee to select January 15, 1559, for her coronation. His selection of this time likely contributed to Queen Elizabeth’s long and prosperous reign (1558-1603). Dee’s selection of such an auspicious time also assured him a favored position in the royal household.

Shakespeare’s Plays

Astrology is alluded to hundreds of times in Shakespeare’s plays and is often critical to the plots. The words and attitudes of the characters reflect his astrological knowledge. Plus, the language of astrology allowed him to poetically reach his audience because it was a language both the groundlings and gallery understood. Below are some examples.

The Tempest

In Act I Scene 2 of The Tempest, Prospero says, “I find my zenith doth depend upon a most auspicious star, whose influence, if now I court not, but omit, my fortunes will ever after droop.”

Henry VI

In Henry VI Part 2, just before his murder, the Duke of Suffolk says, “A cunning man did calculate my birth and told me that by water I should die.”

Much Ado About Nothing

In Much Ado About Nothing, Benedick, who is trying to compose a love poem to Beatrice, laments, “I was not born under a rhyming planet, nor I cannot woo in festival terms.”

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bottom calls for “A calendar, a calendar! Look in the almanac. Find out moonshine …”.

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Julia, speaking of Proteus’ faithfulness, says, “truer stars did govern Proteus’ birth.”

All’s Well That Ends Well

In the first scene of All’s Well That Ends Well, Helena refers to Parolles as being “born under a charitable star.”

King Lear

In Act 1 Scene 2 of King Lear, Gloucester shows his eagerness to blame his son Edmund’s treacherous behavior on the stars: “These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us: though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet nature finds itself scourged by the sequent effects: love cools, friendship falls off, brothers divide . . .”

To which Edmund responds: “This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are sick in fortune (often the surfeit of our own behavior) we make gaiety of our disasters the sun, the moon and the stars; as if we were by necessity, fools by heavenly compulsion, knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance, drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence, and all that we are evil in by a divine thrusting-on, and admirable evasion of a man to lay his goatish deposition to the charge of a star.”

Shakespeare and the Stars

If you want to know more about how astrology influenced Shakespeare’s writings the video below is a great place to start. In the video Priscilla Costello talks about Shakespeare’s obvious and subtle use of the archetypal language of astrological symbolism. Costello is lecturing in a bookstore to promote her 2016 book, Shakespeare and the Stars: The Hidden Astrological Keys to Understanding the World’s Greatest Playwright.

Like most during the Elizabethan Era, Shakespeare was well-versed in astrology. However, he was also somewhat skeptical that it was the be-all and end-all of everything. Perhaps this is best expressed in the play Julius Caesar, when Cassius says, “Men at some times are masters of their fates; the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings.” Here, Shakespeare seems to be saying there is “something” fated about life, but we can do certain things to change it.